Deep in the belly of Kampala, the nation’s capital but also physically the largest city in Uganda, we hear a rumbling. With a cathartic intensity owed to a home-grown, chaotic and rebellious underground: the Nyege Nyege musical platform and its rowdy festival; the success of a band like Nihiloxica, recently signed to Crammed Discs and championed by Aphex Twin… The world over, all eyes are on Kampala right now. But the first to put the spotlight on their city were neither the ravers, nor globetrotting musicians in search of enlightenment. They are more punk, and much crazier. Kampala shines brightly today thanks to a former group of kids from the slums passionate about kung fu, Chuck Norris and Para-SF commandos.

Around fifteen years ago, Isaac Godfrey Geoffrey “IGG” Nabwana, originally from Wakalinga, a destitute district in Kampala, dived deep into the “7th Art”. He was totally broke, totally self-taught, nearly thirty years old, and began to start shooting a few videos for local musicians, before embarking on creating his true masterpieces: action feature films.

Isaac is vividly passionate about action movies from North America and Hong Kong. He cites his idols as being Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Lee, Bud Spencer and Jackie Chan. His objective is simple: to take over and bring down the global film industry with the entirety of his weight, solidly entrenched – but armed and ready for action – from his Kampala slums.

200 dollars for a happy apocalypse

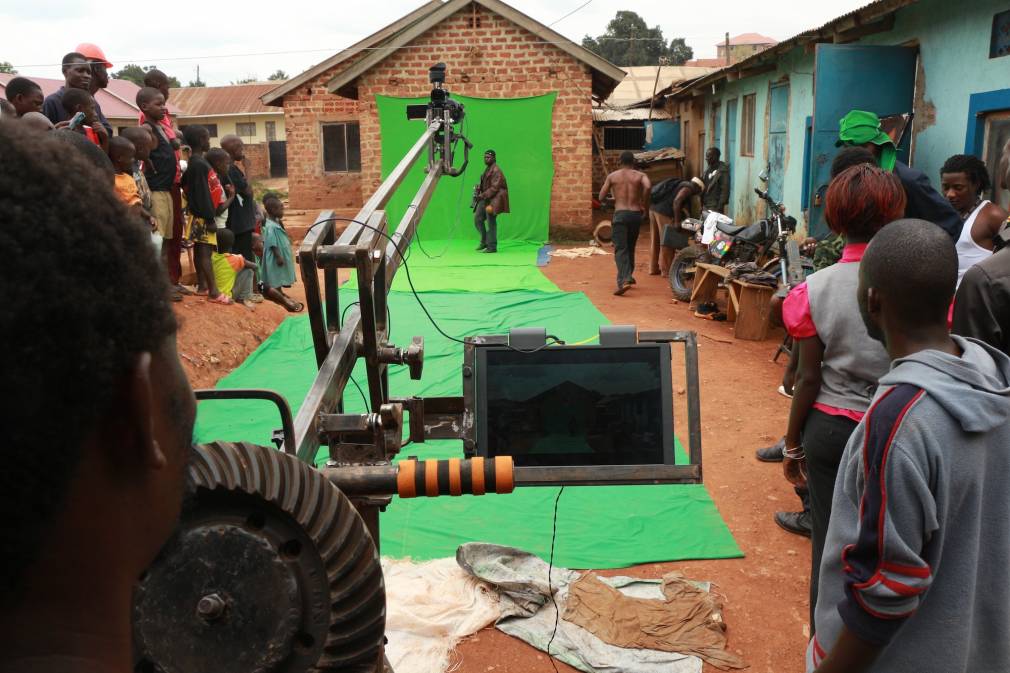

In order to conquer the global cinema industry, he followed a basic rule from free-market economics: before going international, you must first conquer the domestic market. Easy: he created Ramon Film Productions (RFP) – in honour of his grandmothers Rachel and Monica, who raised and protected him from the Ugandan civil war, a guerrilla war that raged from 1981 to 1986 – going on to then shooting his first films right in the middle of the neighborhood. The actors and extras of the RFP-produced movies are his neighbors and the children of Wakalinga. Sets made up from waste materials – using a bunch of metal tubes or frying pans to simulate a rocket launcher, monstrously low-tech special FX, black market distribution, hand-painted posters… the true heights of creativity. With Mumbai’s Bollywood and Nigeria’s Nollywood, the small Ugandan district quickly became known as Wakaliwood and fostered an outdoor filming studio experience for truly DIY action movies. The films are performed by the neighborhood and for the neighborhood, loaded with Ugandan kung fu, drug dealing gangs – the recurring Tiger Mafia – alongside supervillains drowning in pools of fake blood.

From Who Killed Captain Alex to Bad Black via the latest in-house production of Crazy World, Isaac’s films have become true cult hits in the suburbs of Kampala: “all the kids in the neighborhood became Martial Arts fans,” explains Alan Ssali Hofmanis aka “Supa Commando”, a New Yorker who moved to Wakaliwood after watching the first fifty seconds of the Who Killed Captain Alex trailer. The first Mzungu (“Westerner”) turned movie star in Uganda, Alan has been at the heart of the Wakaliwood adventure for almost a decade now: “Who Killed Captain Alex cost just two hundred dollars back then.”

“We then built a Supa Choppa, a fake helicopter,” adds filmmaker Isaac Nabwana. “We would shoot whenever we had enough space on our hard drives. Today we have better gear, but things are still the same: we kill everyone equally! We always work with the same proximity and intimacy. However, we feel that we are reaching a limit with the DVD format, the medium with which Wakaliwood developed itself through a lot. Online streaming will take over shortly, and we’ll be ready for it!”

“As for the rest of it, what has really changed is the way the world looks at us now!” responds Alan “Supa Commando”. Here is the big difference. Our films have been screened all over the world, and celebrated at a number of festivals. The world knows Wakaliwood now. We have fans from Brazil to Norway, it’s amazing!”

When art from the slums begins to upset the elite

At the We Are One Festival, from May 29th to June 7th, 2020, – an online festival on Youtube that brought together some of the most important festivals in cinema together online, from Cannes to Sundance via Toronto’s TIFF and Venice’s Mostra, its opening was prominently pronounced by Isaac and his gang of Ugandan kung fu fighters: “There is something huge happening for us right now,” adds Alan, also in charge of translation of all subtitles for RFP. “The Wakalinga ghetto, a third world inside the third world, is becoming an international phenomenon. It’s unexpected.” On Youtube, Wakaliwood literally blows up with view stats: a recognition that carries its share of questions. “We are becoming recognised as a national cultural movement. This dynamic and success disrupt the archaic practices of the ruling class which has ignored all of its social bases. In fact, today we are moving with caution, because we understand that we are upsetting the institution,” says Alan.

Here, the elite resent the slums seizing cinema as a tool to express itself. The neighborhood of Wakalinga and Isaac’s films truly break down this system of institutionalised cultural dominance. For Alan, “Uganda is a very conservative country, with extremely rigid tribal diets and clothing. Community bonds are meant to be maintained through a hairstyle, one and the same for all!” The Wakaliwood scene is led by genuine punks who are ripping up the rulebooks. “In 1977 in England, when the punk-rocker Sid Vicious became the UK’s international ambassador, the Queen was not laughing. It’s the same here. As much as our films are not political, as in we do not explicitly criticize our leaders, but let’s say if the price of raw materials increases in Uganda, then it will be addressed at some point in a scene.”

This subversive and social commitment naturally expressed here has become powerful and unifying. In a Wakaliwood film, the use of local slang is common, led by a continuous voice-over from the griot – supplying non-stop jokes –, with a focus often concentrated around weapon trafficking, mafia networks and mysterious disappearances. The similarities – although unconscious – with the regime of the former dictator Amin Dada are numerous, with the Ugandan police being regularly mocked. Isaac’s productions are committed to celebrating the ways and identity of Wakalinga’s slums, yet they are still able to unify and resonate thanks to the power of values they transmit and promote, allowing for large parts of Africa’s youth to be able to identify with it: “This is the reason why we are so popular here. This is also the reason why the ruling class, completely disconnected from its people, is watching us from afar, with contempt, for sure, but also with fear, the same as when you watch the beginning of a fire starting. The only reason the Ugandan press has come to Wakalinga is because the CNN, the BBC and Time Magazine have already come to visit us previously. But know that Ugandan journalists, when they visited our ghetto, did not even dare to sit down for fear of getting themselves dirty. In Uganda, racism and social segregation are operating at unprecedented levels.”

Wakaliwood finds its following

After more than fifteen years of usurping the industry, Wakaliwood is still grappling and looking for a new place in which to set up its gear. Still locked down at the time of when we wrote this piece, the filmmaker is struggling to organize his films with the current social distancing guidelines. Their massive international screening tour was postponed until further notice. Directors Cathryne Czubek and Hugo Perez have just released the documentary Once Upon a Time in Uganda dedicated to the work of Isaac. The film was meant to celebrate the glory of Kampala at the legendary South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, which was also canceled this year due to the global pandemic.

For Alan, the next chapter will be dedicated to international collaborations: “Wakaliwood is a worldwide thing, so let’s tear down all cities all over the world!” For Isaac, transmission that has become more relevant than ever: “Since the beginning we have taught a lot of filmmakers, we train young people up as set designers, make-up artists, stunt performers and actors. Today, a whole new generation of kids are ready to pick up the torch. The future of Wakaliwood cannot happen without us opening up our studios to the outside world, as well as with our directors.”

In the meantime, Isaac and his family meditate on the unanswered question of how long this lockdown will go on for: they are responsible for an entire cinematic ecosystem, which must survive in order to keep growing. But with the end approaching, everyone can be sure of one thing: everyone will be killed equally.

Surf on the waves of never-ending ammunition fire and nuclear blasts at www.wakaliwood.com, a true masterpiece of NetArt.